In the past, when no one had ownership rights over natural resources, all living beings, both animals and humans, shared everything collectively. No one was prevented from taking what nature provided, just as no one stops birds from living off what they find in nature. People relied on what was immediately available and had to survive with it. Everyone thus had a foundation that was their guarantee for survival. However, that is no longer the case for us humans. Not everyone now has free access to such a “foundation” (i.e., means of subsistence) to rely on.

The country’s resources – both land and sea – remain the “foundation,” or in other words, the basis of existence for all of us. It is what society is built upon. Without it, we would starve. But today, almost all natural resources have been privatized and expropriated. Everything is managed by private hands or by state authorities, as the resources that have not yet been privatized are considered by the authorities to be under their control.

This means that access to the resources we once all shared before they were privatized or expropriated is no longer freely available to most people. Some have acquired the “right” to deny others access to resources that were – and still are – the basis of existence for everyone.

What Does “Public Property” Mean?

Many have forgotten what the term “public property” signifies and why it is called that. We no longer, or rarely, reflect on the fact that what is not yet in private hands belongs to no one in particular. Thus, we all own it equally – just like we “own” the air we breathe every day. Hence the term “public property”. But it has been so long since almost everything was taken over by someone that we’ve forgotten how things were before and cannot imagine the world any differently from how it is today.

Individuals who now hold a significant portion of natural resources claim they deserve to own these assets because they, or their ancestors, did substantial work and invested much in these resources, believing they have full historical rights to own them.

But what does this actually mean when considering the consequences privatization has had for everyone else? For those who received no part of the natural resources, privatization has meant that they and their descendants no longer have the same guarantee of livelihood as their ancestors did. They were never assured that anything of equal value would replace what their ancestors once relied on and to which they now have lost access.

Even though their descendants, who are without property, had no influence on nor are to blame for their current situation, they still suffer because their ancestors somehow lost access to resources, leaving almost nothing behind. As it stands, they cannot reclaim the rights their forebears once had. Property rights, according to the constitution, are inviolable. This greatly benefits those who happen to inherit resources once acquired by their ancestors, despite not having personally done anything to own such property.

The reality is that, historically, no one asked others when resources were originally acquired. In many cases, there were no protests—likely because there was an abundance to take from, and seizing property wasn’t a significant issue. If any did protest, they likely had no chance because they were either overpowered or were persuaded to move for a small sum, unaware of the true value of what they were giving up, thereby binding their descendants in perpetuity. Or they were simply killed! Think of the indigenous peoples in America. But now, with almost all resources claimed, we suddenly face a problem.

Modern Slavery

Unless they have chosen to sell everything, the heirs of the “property holders”—those who originally acquired the resources—now possess all these essential assets simply by inheritance. In theory, they can retain these rights generation after generation—potentially forever. If they do decide to sell, only those who are already relatively wealthy can afford to buy. As a result, over time, almost exclusively wealthy individuals—or those with property rights over land or sea—end up owning or having exclusive rights to nearly everything others need to live.

The fact remains that everyone still needs something to live on, not just the descendants of the original property holders. Now that the propertyless can no longer freely use natural resources for their livelihood, what are they supposed to base their existence on? What should they do to survive?

For most people starting from nothing, the only viable option is to offer their labour to those who can afford to pay them wages. However, this requires them to submit to the conditions set by the employer. Since they cannot do without wages to survive, they must, in exchange, relinquish many of their rights.

They must, for example, accept that they no longer have full freedom and control over their time and do not decide what to do or produce during working hours. Nor do they own what they produce. Others hold the property rights over it, as well as over the majority of their time and energy. In reality, they have become someone else’s property—at least during working hours, which occupy most of their waking hours and consume most of their energy.

However, a large portion of the entire workforce earns just enough to convince themselves that they have some freedom—probably to prevent excessive dissatisfaction and thus potential uprising. This way, it becomes less visible that most of the propertyless are forced to live at the mercy of others and under conditions set by others, including a myriad of laws and regulations that state: “No, you cannot do this, or cannot do that either, because someone else owns or has all the rights, for instance, to that land or that fishery resource.”

Yes, wage levels and material wealth have increased over time compared to the past—even for the lowest-paid workers. But it remains true that a large part of the population faces more or less constant economic challenges, even though they work themselves to the bone daily through nearly their whole lives. Yet, they barely make ends meet, surviving from paycheck to paycheck, many without ever affording their own roof over their heads. And they constantly have the threat looming over them that if they lose their job or cannot earn enough this month, they could lose their home and end up in poverty. An unexpected bill could make all the difference.

Caught in a Cycle of Poverty

Of course, one can point to a certain degree of social mobility, where a few propertyless individuals have managed to fight their way out of poverty and climb the social ladder—perhaps through sheer hard work or luck, or both. But this is the exception. Far from all the propertyless are able to start their own business and/or convince investors to fund their projects. And not all possess the skills or energy to complete an education that might lead to better, higher-paying jobs, as their starting point is worse and they start far below the starting line of the more wealthy.

For many without property, the choice often lies between taking the lowest-paid, least attractive jobs that few people want, or being unemployed. If their income is too low to buy or rent a decent home, the choice is between living in poor, possibly unsafe housing that they cannot afford to maintain, or ending up homeless on the streets. When people are in such a pressured situation, they don’t have many options. Unless they choose to try earning money through crime, which often lands them in an even worse situation, they have to accept society’s conditions and take whatever they can get in exchange for their labour. They are even expected to be humble and profoundly grateful just to have the chance to work, and to be content with the few resources they receive in return. It’s better than nothing, isn’t it?

This way, many people are controlled by those with more power than them. Currently, most propertyless individuals have few options to secure essentials like food, clothing, and shelter without sacrificing their freedom. They either ‘get the chance’ to work for resource owners, ‘get the chance’ to rely on public welfare, or ‘get the chance’ to borrow from banks, often struggling for a lifetime to repay with high interest. The powerful, to whom the propertyless sacrifice most of their freedom, become richer and gain more control over everyone else’s conditions. If all do not comply with these demands, poverty is inevitable.

From this perspective, isn’t it somewhat ironic that those who employ others in many languages (like the Nordic langugages – are called “work-givers” (employers) as if work is a “gift” they provide? Meanwhile, those who labour are called “work-takers” (employees,) as if they are “taking” something from those they work for? Isn’t it actually the opposite? That workers “give” their labour, while those they work for “take” their labour? This way of framing these relationships reveals who truly holds power in society and whose interests we deem more significant.

These are the conditions many propertyless individuals must endure, conditions they never asked for. Their ancestors lived without these constraints, when land and sea were freely available for everyone, and all could naturally obtain life’s essentials without obstruction.

Discrimination against People

A significant portion of the population is forced to live under harsher conditions with less freedom than the fortunate individuals born into better-off families that can provide financial security from the start. These different starting points create an uneven playing field where not everyone has the same opportunities from birth. The fortunate enjoy more freedom, as they are not compelled to work for others to survive to the same extent. They also have better opportunities to pursue longer education. Often, they receive better support from home because their parents may also be well-educated and well-off in other ways.

Those without these advantages must struggle much harder to overcome their less favourable starting point. If the propertyless are to afford education, they must spend a lot of time working alongside their studies. Naturally, this means they cannot focus as much on their studies as those who do not need to work. Additionally, they often receive no assistance from home—neither academically nor financially—because their parents are unable to provide it. Understandably, it becomes harder to succeed under these conditions. Therefore, relatively few of those who lacked advantages from birth manage to rise above their heavier social inheritance to achieve a level of independence where they set their own terms rather than others.

Although no one, from an ethical standpoint, is inherently more worthy than another, our societal structure permits distinctions between people. If individuals express dissatisfaction with this inequality, they are quickly accused of being negative, envious, or simply lazy for not wanting to do what it takes to lift themselves out of poverty. Meanwhile, the advantages and privileges enjoyed by those from wealthier families are overlooked, even though they rarely have a personal claim to them more than others. They are merely born into more resourceful families and thus have a head start over those who must begin from scratch or less.

Dependence on Welfare Keeps People Down

It is a fact that inequality, lack of freedom, and poor living conditions lead to illnesses and poor mental health in society. There are numerous examples of how some individuals lose their footing under the pressures current society imposes on us. It is all too easy to lose balance. Fate can, for instance, strike some people hard for reasons beyond their control. Illness, death, divorce, and similar events can cause stress and depression, rendering people less equipped to meet the demands of society and employers. They may lose their jobs and, consequently, the income they need to survive.

Some receive public welfare support, but only if they meet certain – often very strict – conditions. The problem with receiving wellfare assistance is that recipients become stigmatised and often looked down upon by others. This negatively impacts their self-perception, making them feel even more broken. Most people undoubtedly prefer to fend for themselves, avoiding the label of ‘freeloaders’. However, once in the support system, it is not easy to escape it.

The issue is that people cannot rebuild themselves overnight after a personal crisis and immediately return to full working capacity. But in the eyes of the authorities, there is often no middle ground. One is either unemployable or capable of working full-time. Those not entirely ready for full-time work get trapped in the system because they depend on the welfare support. They feel obliged to continually prove their unemployability; otherwise, they risk losing the only income they have, so they dare not do otherwise. It cannot be particularly uplifting for one’s self-esteem to constantly have to prove how incapable they are of working.

On the other hand, it doesn’t encourage a stronger work ethic if you’re economically penalised for showing initiative. You might want to use your unemployment period to slowly build a small business based on your passion, which could eventually lead to establishing your own company and becoming your own employer. But no, you can’t do that— not without losing your guaranteed income, because you MUST be available to the job market for other employers to receive unemployment benefits. The system thus forces you to either sit idle or take a job imposed by the system, which you did not seek and may have little motivation to perform because you know it’s not the best use of your skills and abilities.

The result is that many people receiving various forms of public assistance end up in a sort of limbo or standstill. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. There’s also the risk that the longer you’ve been out of the job market, the harder it is to convince employers that you’re worth hiring. It doesn’t look good on a CV. The outcome is that some individuals involuntarily get trapped in a vicious cycle of long-term unemployment, which they find difficult to escape.

Some people fail to meet the requirements set by authorities to receive support and therefore get nothing. But they also can’t work – or find no suitable work – and must live in deep poverty. This leads some to desperate actions, like substance abuse or crime, which unfortunately only results in more desperation and misfortune. A vicious spiral that could ultimately cost society a lot of money.

Inequality in How Much It’s Worth to Work

It is often said that work should be rewarding, and that sounds fair enough. However, the reality is that the benefits of working vary significantly depending on who you are and your circumstances. Some individuals receive a lot for little or no work, while others get little or nothing in return for much work. Many people without property may work much harder than those who don’t need to work as much because they already own so much.

Some might argue that we just have to accept this because, without wealthy employers, workers wouldn’t have jobs where they could create the values that enrich society. Therefore, employers are deemed “more valuable” to protect for society’s sake. On the other hand, no values would be created without the workers. So, who is truly more “valuable”?

Although in many cases, propertyless individuals may work more, produce more, and hence create more societal value with their labour compared to others, they still do not reap the same benefits from their work. The wages or fees received by different groups often do not correspond to their work effort. The distribution is not balanced. Far from it.

For most of us, life’s conditions have been this way for so long that it’s now considered natural to have such significant differences among people. We’ve lived with this for so long that we’ve started seeing inequality as “natural.” We convince ourselves that those worse off than others are entirely responsible for their situation. Poverty is seen as so natural that many believe people are solely to blame if they can’t make it and fall through the cracks, and thus don’t have the right to demand a guaranteed income.

But this doesn’t quite add up, as we simultaneously think it’s perfectly acceptable that others are guaranteed a lifelong income just because they happen to be born into a wealthy family that may have accumulated riches over many generations. Referring to the biblical phrase “those who have, will be given more”… Some indeed have far more freedom and financial security from birth than others, without having lifted a finger for it. Are these fortunate people in their elevated positions because they deserve it? Are they somehow born more “worthy” than others?

Of course not. Far from it. Kings and queens may seem more “worthy” than others, with their grandeur and lavish residences, but they are, of course, humans with both good and bad traits just like the rest of us. No matter how high a pedestal we place them on, their blood doesn’t become any bluer. The truth is, they can only sit on the throne as long as the rest of us accept them being there – yes, as long as no one dares to shout that the emperor has no clothes.

Solidarity frees us as human beings

Why is it that many find it acceptable to grant some people unconditional financial security for life, without them having to do much to earn it through their own labour, while denying this unconditional financial security to other hardworking individuals who have fully earned it?

Why should some people’s right to a dignified life be valued higher than others’ simply because they were lucky enough to be born with advantages that others lack? Is it acceptable for a significant portion of the population to live in poverty or on the brink of it, even when working full-time? Do the less well-off not have just as much need – and right – to be protected from poverty as anyone else? Do they not also deserve basic human rights to live a free life on their own terms, even when they find themselves in an involuntary life crisis?

If we choose to ignore and not solve the issue of poverty, what does that say about us? What does it say about us when we consider some people’s work to be less valuable than others’, even though both parties may create equally important contributions to society? This consideration extends beyond mere “economic returns” to include everything people do to care for each other, which is at least as important – if not more – for how well a society can thrive and withstand crises.

Care work is often undertaken by the less affluent. What does it say about our perception of true value when we view such work as a societal expense and fail to recognise its profound social significance? What about all the unpaid work relatives do, such as looking after their own children or caring for elderly or sick family members? Why isn’t this work acknowledged as socially beneficial and at least paid well enough so that those who perform it can live as freely and independently as those with economic power?

Many argue that people should be grateful simply because we have employers who can hire them—expecting gratitude merely for the opportunity to work. So, be thankful for what you’re offered. It could be much worse, right? Isn’t unemployment a far worse alternative?

What about the gratitude of those who enjoy the privilege of avoiding the work others do for them, often unpaid or poorly paid, allowing them to maintain their free, privileged lives? What does it say about those who seek a freer, more independent life for themselves, yet don’t wish the same for others?

The Cornerstone of the Welfare Society

Some might call this cold-hearted cynicism, or even elitist, self-centered glorification, and yes, outright abuse of power. The truth is, no one can manage without others. No one can achieve wealth entirely alone on a deserted island without the help of other people.

It may be hard to grasp for modern individuals, who today highly value individualism and independence, that it is our community and solidarity that genuinely enriches us all, elevates each person, and liberates us as human beings. One person’s needs are another person’s livelihood. Without solidarity – indeed, without what we do for each other – we do not survive. It is our actions for one another that substantially give life its meaning. There’s also the question of whether happiness can truly be happiness if it is built on the misfortune of others.

Therefore, it is crucial to be aware of and appreciate the significant impact we have on each other as citizens, despite all differences. This mutual bond is one of the most essential cornerstones of society’s prosperity, which is again a foundational component of the democratic welfare society and, in general, has made it possible to create the wealth of the entire society.

Shouldn’t we – we, who together have created this prosperous surplus society – ensure that no one needs to live in fear of falling into poverty?

Inequality Deprives People of Their Freedom

Poverty is a significant societal issue – not only for the poor themselves but also for the entire community. Poverty not only drains the poor of their energy but also increases the risk of diseases, mental disorders, and crime, which cost society many resources and money, dragging down the whole community. Although the current social system has become more cohesive over time and provides better living conditions for most people – partly thanks to the efforts of the trade union movement – there is still a long way to go before we can say that our social system truly protects individuals from poverty and its associated problems.

Is society truly “free” when citizens live under such unequal conditions? Is there genuine democracy as long as the majority of the population must constantly live under the threat of poverty if they do not submit to the terms of a wealthy elite, who believe they have more “right” than others to possess our common resources and thus have the power to set the agenda for everyone else?

A significant obstacle to solving the problem of poverty is precisely that nearly all natural resources, which are the foundation of life for all of us, have become the “property” of a few. Those who have secured or inherited these resources claim the full right to control these resources and the values that can be extracted from them. They also claim the right to decide who can share in the values and who cannot – thereby determining how the societal wealth is distributed. But who granted them this right?

It is hardly possible to do anything about the sacred property rights, but why should all the income from the exploitation of natural resources, and the values that so many others help to create from these resources, primarily benefit a few who claim historical exclusive rights to these values? What does this mean for everyone else?

We must understand this: The lack of ownership in resources fundamentally deprives people of their freedom and essentially makes them slaves because, to avoid poverty, they have to relinquish much of their self-determination just to be “allowed” to live off the grace shown by those who own the rights to the resources. This becomes a fundamental issue when the threat of poverty weighs heavily on so many. Are people then truly free?

The fact is, this does not have to be the case. This is merely one way we have organised our society, and it can be changed. It is possible, if we genuinely wish to reduce inequality, eradicate poverty, and enhance individual self-determination and freedom.

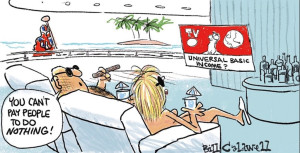

Basic Income Guarantee – A Human Right

Had no one initially claimed resources and made them their property, thereby depriving others of their livelihood, people wouldn’t have been forced to submit to others’ power to survive – in other words, there wouldn’t have been slavery. Now that there is no longer free access to resources, which are essential for everyone’s existence, isn’t it a human right for every citizen to have an alternative guarantee – a different foundation to rely on? Economic security? Especially in a society as wealthy as ours – one of the richest in the world?

The question is, don’t all citizens have a right from birth to a share of our common means of subsistence? This doesn’t mean that everyone must be forced to be exactly the same. It simply means that if everyone had a right to a portion of the wealth created from what was originally “the people’s property,” everyone could be fundamentally protected against poverty. And this benefits society as a whole.

We must understand that as long as everyone does not have free access to society’s resources, there will not be true freedom for anyone except those who possess those resources. This is unless they provide an unconditional compensation for what they own, which can liberate all dispossessed individuals to live as free people on their own terms, without fear of stigma or falling into poverty if they don’t submit to others.

An unconditional basic income for every citizen would restore freedom to everyone, giving people a genuine choice in how to use their time, energy, and skills.

It may be challenging to imagine that this is possible. The first question that often arises when discussing the provision of a basic income to all is: “But who will have to ‘bleed’ or ‘sacrifice’ so that others can receive a basic income for potentially doing nothing? Nothing is free! Nothing comes from nothing.”

Indeed, nothing comes from nothing. However, it is a misconception that those receiving a basic income are ‘taking’ something from others. Some believe that individuals on a basic income will simply stop working and producing the societal value we all rely on, choosing instead to do nothing. But that is not what happens. Most people do not suddenly become lazy, as some fear. On the contrary! All experiences to date with providing basic income show that when people are not compelled to work for others just to survive, they often work and produce even more than before because their work holds more meaning!

How can it be? The reason is that when people are given the opportunity to spend their time and energy on what they truly desire, they become even more motivated to work and be productive. It makes much more sense for people and is far more motivating to work when the effort is directly beneficial for themselves and their loved ones, rather than for an employer who only sees them as labour for personal gain and is otherwise indifferent.

The belief held by many today that money is the sole motivator for work is linked to the current societal system, where people are forced to work for money in order to survive. It is hard for us to imagine how it would be if people were guaranteed a basic income to cover their living expenses, making money less of a concern. If individuals were assured a basic income regardless of whether they worked or not, work would not just be something done to earn money, but something pursued primarily out of personal interest and deeper meaning—doing it to enhance both their own lives and the lives of others. And it actually seems to work and be so effective that people become even more motivated to work.

Not Like Stifling Communism

Experiences with implementing unconditional basic income for citizens show that it releases a lot of energy, which benefits society in diverse ways. It does not remove the incentives for people to work and be productive. On the contrary, it gives people more motivation to work because they can choose what they want to do and gain more from their work.

This is not about – as in communism – abolishing private property rights and suppressing all private initiative by prohibiting ownership, equalising everything, and keeping everyone at the same (low) level throughout their lives with no differentiation. No one is saying that people should not be able to become wealthy. That is not the intention of unconditional basic income – quite the opposite. Unconditional basic income is about ensuring that everyone has fair opportunities from the start, so no one is born into poverty and kept in it. Everyone should have the chance to develop themselves according to their own wishes, including the opportunity to become wealthy if they desire.

If EVERYONE – not just a select few – is guaranteed a financial foundation from birth, without the need to meet any conditions and without the stigma associated with welfare / social assistance today, it provides not only a few but everyone the best possible chance to develop themselves and their skills. This way, people can spend their lives doing what they are best at and enjoy the most. This also applies if their goal is to become wealthy, provided they are capable.

Ensuring that the country’s citizens have a basic income does not prevent those who wish to become rich from doing so – it only ensures they cannot become wealthy at the expense of others. Those who deserve wealth are the ones who have worked hard for it and created significant value through their own labour, talents, and abilities. They haven’t simply benefited from what others have created through blood, sweat, and tears – often using resources that originally belonged to everyone but now predominantly benefit a few, despite many contributing to creating this value.

An Investment We Make in Each Other

The question of who should “bleed” for others is wrongly posed. The truth is that most people are currently “bleeding” so that a few rich individuals can stay wealthy. Many sacrifice all their time and energy in ways that benefit others more than themselves. Basic income security is not a gift that some (the rich) are forced to give to others for free; it is something we ALL provide to each other, and everyone benefits from it—directly or indirectly. If everyone receives basic income security—both rich and poor—no one who truly creates value through their labour will “bleed” more than anyone else. In fact, they will do that so much less than they do now.

We must understand that everyone has value and that EVERYONE has something to contribute—not necessarily always economic values, but fundamental values for society. Basic income guarantee is an investment we make in each other, which ultimately benefits everyone. It is about recognising why everyone deserves economic stability. When people are freed to primarily take care of themselves and their loved ones and use their talents to the fullest, they flourish and have the capacity to contribute significantly. This greatly benefits society, but according to individuals’ own wishes—not just to fill the pockets of a few.

A basic income would liberate everyone from having to take on slave-like work for excessively low wages. It grants them the freedom to refuse jobs that do not pay according to the true value of the work produced. If everyone was guaranteed an economic foundation to rely on, they would have far better opportunities to build lives according to their own desires, where they could be productive and live freely on their own terms rather than someone else’s—even if they were involuntarily hit by life crises occasionally.

Imagine all the extra energy and the myriad of talents that would be unleashed if everyone were granted the freedom that economic security provides, no longer needing to spend almost all their time and energy on often pointless or meaningless work that they must undertake just to survive, work that benefits no one but others—perhaps even complete strangers.

A basic income for all frees people from this form of slavery. Providing this human right to everyone has nothing to do with envy or taking away from others. On the contrary, it is about restoring to people something they were originally entitled to simply by being born into this world. In essence, it is about returning to everyone the right to self-determination and freedom.

But Can Society Afford It?

If we view the payout of basic income security to citizens as a pure public expense that taxpayers have to “bleed” for, it may seem unrealistically expensive to give every single citizen a monthly amount to protect everyone from poverty. But that’s not the right perspective. The basic income doesn’t cost each citizen the same amount they receive in basic income. How does that work?

To calculate the cost of basic income guarantee, we must consider that it reduces other expenses — as shown by experiments with basic income guarantee so far. Basic income guarantee lessens the need for conditional public benefits. In reality, many current public expenses are saved because many conditional benefits cease when basic income guarantee often replaces these benefits. A system of basic income guarantee reduces the need for existing welfare services, tax subsidies, or social support systems. People with secured basic income are healthier and require less medical care. People with secured basic income commit fewer crimes, so expenses on trials and imprisonments are reduced, and so on. In short, basic income guarantee means spending more so that overall, we end up spending less.

But what does that mean? Imagine you are the CEO of a car company, and the management team informs you that costs per car can be reduced by DKK 10,000 if the company invests an additional DKK 1,000 per car engine. It would not be a good managerial decision if, as the CEO, you decided to save the DKK 1,000 per engine, believing it would reduce the final yield.

In reality, the true cost of ensuring a basic income for all citizens cannot be calculated by assuming the absence of a basic income is the same as zero. Poverty is not free. Persistent economic insecurity among people is not free. This is why it is considered that when the tax system provides child allowances to people, it is absolutely worth it because the investment pays back to society. If parents also received a basic income, the return on investment would undoubtedly multiply. Therefore, one can say that the cost of a basic income for every citizen is a sensible investment that ultimately benefits society as a whole.

(See source: https://www.scottsantens.com/how-to-calculate-the-cost-of-universal-basic-income-ubi/)

Dividends for Ordinary Citizens

We must also remember that production in society has multiplied manifold in the past one and a half centuries, largely due to increasingly advanced technology that is developing at an accelerating pace. Artificial intelligence (AI), in particular, can now produce various items in minutes, or even seconds in some cases, whereas humans would have previously taken weeks or months to do the same. However, the surplus from this significantly increased overall value creation in society far exceeds the average earnings of ordinary citizens with normal wages.

Society as a whole benefits from these advancements—items such as a coat, which might have once cost an entire month’s salary, have become more affordable. Yet, most of the economic gains from these advancements end up in the hands of a few. Ordinary citizens do not equally share in the real added value created by technological progress, nor in the additional value of their own work or personal data. The largest companies in the world today profit enormously from collecting personal data, which they acquire for free from people.

Hardworking individuals, who have significantly contributed to the creation of this wealth, often have to get by with very little because most of the returns from their value creation go to companies or shareholders as profit-sharing dividends. The surplus or profit from the total value creation in society is simply appropriated by the wealthy, with much of it accumulating in tax havens like Belize, Bermuda, the Marshall Islands, or others, as revealed by the Panama Papers scandal in 2016. There is little evidence that this practice has changed since the scandal.

The shareholders who benefit from the profit distribution were not the only ones to create this added value. Others have certainly also contributed to creating what shareholders primarily benefit from. Do not all those who generated this value deserve a share of the profit? Or should this profit only favour the few? Why not all citizens? Much of what is produced would not be possible without our highly functional, well-organised, well-educated, advanced, and solidarity-based welfare state, which all citizens are part of – which everyone pays taxes towards, and thus everyone helps to maintain and develop.

The taxes we all pay ensure a well-operating, well-educated welfare state, which is an indispensable cornerstone for the value creation in society to be as dynamic and advanced as it is, and for it to continually evolve and expand.

To best ensure that no one is left with nothing, a basic income might be introduced for citizens – for example, in the form of a negative income tax. This means that if a person’s income falls below a certain level, they would receive a negative tax – essentially, they get a tax refund – while those whose income is above this level pay tax, thus creating a progressive tax system. (Read more here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negative_income_tax)

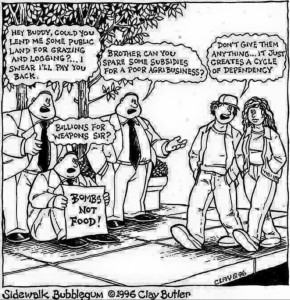

The Trickle-Down Effect – A Myth

Some people believe it is perfectly fine for a few to reap the profits because it “somehow” trickles down to the working populace. They argue that the surplus is used for investments in expanded activities, leading to job creation for “ordinary people.” However, it has been well-proven that the much-discussed trickle-down effect is a myth. In reality, this is not what happens.

In cases where the surplus is not merely accumulated in tax havens, it often goes towards investments in technology and increasing automation of activities. This does not increase but rather decreases the number of jobs. After all, which business owner would not want to gain more from less? Businesses are not just there to create jobs; their primary goal is to make money, especially for the shareholders. So, which business owner would not want to reduce labour costs and instead invest in production tools that can operate 24/7, do not strike, and do not require holiday pay, sick leave, or pensions – thus providing higher returns to the shareholders?

In cases where the surplus does not go towards automation, it might be used to relocate activities to other countries with lower costs and lower wage levels – again because it is more profitable for the shareholders. This also does not create many jobs.

To counteract job losses and prevent economic crises, public authorities often choose to stimulate the economy by investing in large (prestige) projects that create jobs, but which might not be as crucial to society compared to other, possibly more urgent measures. This is an “artificial” injection into the economy to create “artificial” jobs, decided by the authorities. While this work can yield positive results, ordinary citizens have little influence on these decisions, which also affect their lives.

It is a fact that shareholders pay much less tax than regular citizens – often no tax at all. Therefore, society reaps less from corporate profits than it could – money that could have been used to fund better services benefiting regular citizens.

It’s one thing for the wealthy to avoid paying taxes that could genuinely benefit society. But if this money, which ends up in the bank accounts of the rich, were instead to go into the state coffers, where bureaucratic authorities alone decide how to use it, who deserves a share, and which projects tax money should fund, this could also significantly limit citizens’ freedom and self-determination.

If citizens are to have the greatest possible security, freedom, and self-determination, should we not rather consider whether it would be better for as much as possible to be paid out directly as a basic income to every single citizen—without any questions? This way, people can decide for themselves how to use their money and which services they wish to pay for. Most people probably know best what they need or do not need, instead of being told by an authority. They likely wouldn’t choose to spend much of their money on weapons production, for example.

Where Do Money Benefit Society the Most?

Instead of profits ending up in the bank accounts of the wealthy or just in the state treasury, where only a few powerful individuals decide how the money is used, a basic income system for citizens would ensure that everyone shares the total value generated in society. It’s a way to direct the overall surplus so that more money reaches ordinary people, where it can be most beneficial. Money represents power, and better distribution of money ensures that power is also more equitably distributed among the citizens, rather than being concentrated with an elite.

When a citizen receives a basic income, the money doesn’t just disappear into a black hole. Basic income stimulates the economy, especially locally, because the money is spent on daily necessities, rent, home and car repairs, services like hairdressing and personal care, and purchasing experiences, arts, and cultural goods. This increases the likelihood of creating genuinely needed jobs. By providing a basic income, we not only protect ordinary people from poverty but also significantly encourage private initiative and small businesses, which can help improve the level of services for everyone.

When there’s more money to be made, it also encourages people to produce more, as basic income motivates everyone to consume more. When money thus truly circulates in society and doesn’t just end up in the black holes that tax havens effectively are for the rich, each individual citizen benefits much more. Money in circulation among people creates greater social utility — more than if it were just frozen in a few accounts or only used for investments in large corporations’ technology development, or for massive state investments in projects over which ordinary people have little influence and from which they may gain questionable benefits.

The rich also benefit in the end, as the increased production makes the whole society wealthier. Particularly now, with technology and technological equipment becoming much cheaper, ordinary people can afford production tools that previously only the wealthiest could buy. This makes it more feasible for many to produce almost anything at home, in their basement or on their desk, to sell and live off. Therefore, fewer will need an “employer” in the same way as before, when they depended on working for someone who could pay them a salary.

The Uncertain Gig Economy Increases the Need for Basic Income Guarantee

We have entered the “Gig Economy” era, which refers to a labour market dominated by freelance work and hourly jobs rather than permanent positions. Gig workers are often self-employed entrepreneurs, people working in information technology, shift workers, temps, Airbnb hosts, Uber drivers – essentially, individuals working mainly under short-term contracts, agreeing with clients to deliver specific services within a given period “on demand.” We’ve seen significant growth in online services like Airbnb, Uber, and Lyft, where private individuals provide services to other private individuals.

However, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck the world, it became clear how vulnerable the economy is – especially the gig economy. Many businesses had to shut down, and many people lost their jobs. The world was unprepared to handle such an unexpected challenge. As so many full-time jobs suddenly disappeared, the unemployed were thrust into the gig labour market in search of alternative income sources, meaning the gig economy now risks becoming oversaturated. People also fear that automation will eventually replace the jobs created by the gig economy – for example, driverless cars replacing drivers, robots performing monotonous routine tasks around the clock without breaks, and AI (artificial intelligence) technology overtaking humans in virtually all areas, including creative work.

What was so appealing about the gig economy was its flexibility and freedom. In a way, the gig economy has given ordinary people more self-determination than they have ever had before, but only as long as the gig economy performs well. However, the employees working within this economy face much greater uncertainty and are highly vulnerable. This was demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. They have little to no job security – hence the term “precariat,” which describes those who are part of a class where people lack stable employment and therefore must settle for sporadic tasks and project work available – if any are available at all.

There is talk that more and more people – including those in the middle class – will undoubtedly end up in the precariat over time. Working under the conditions of such an insecure job market means, among other things, that one must always be prepared to make last-minute plans, and income can often be very uncertain, as well as lacking the security that individuals in permanent positions are accustomed to, such as pension, savings, and other benefits. When people do not have a guaranteed steady income, it puts a tremendous amount of pressure on them. This increases the risk of powerlessness and stress among citizens – and thereby also the risk of illness and legal offences.

We have not yet fully seen all the transformative consequences that follow from recent fundamental societal changes. But one thing is certain: societal changes mean that now, more than ever, there is a need for a system with basic income guarantee to prevent the negative consequences of an increasingly precarious job market.

In Conclusion: No Freedom Without Basic Income Guarantee

The current situation reveals that only a relatively small number of citizens have acquired, inherited, or been allocated significant wealth, often by gaining control of natural resources that were originally accessible to everyone and owned by no one. Those who first secured these resources and the right to exploit them became wealthy. They became so wealthy that they could afford to acquire even more. Gradually, nearly everything in society that can generate profit has become the property of a few wealthy individuals, giving them immense power.

Even though natural resources are fundamental to the survival of all of us, the owners or rights holders have the power to deny others access unless certain conditions, set by these owners, are met. Since our shared life-sustaining resources are no longer equally accessible to the majority, most people consequently become subject to conditions from which those born into the right families, or who know the right people, are exempt. The property-less are left to live at the mercy of the wealthy, holding little or no power and thus largely excluded from influencing society. This exclusion persists even if they might be just as capable (or perhaps more so, who knows) of managing or creating value from the resources as those who own them and thereby hold societal power.

If all those without property received compensation for what they have lost access to—namely, the ownership or usage rights of natural resources—this compensation could significantly restore their freedom. But as long as the “owners” claim the entire right to natural resources and the yield or value extracted from them, others do not have the same right to a livelihood and consequently do not enjoy the associated freedom.

Questioning the fairness of some having more rights than others to what fundamentally sustains us all is not about envy. In a developed, affluent, and socially-oriented welfare society like ours, we now have more capacity, opportunities, and means than ever in history to guarantee every citizen the basic human right to an economic foundation. This can be achieved without anyone becoming impoverished. Society can more than afford to provide each citizen with the freedom that economic security, such as a basic income, could offer. The same freedom that the wealthy enjoy today and the same freedom that people had in the past, when everyone had equal access to nature and its resources, and thus a foundation to build upon. A foundation that, today, the propertyless lack, unless they submit to others’ power and sacrifice their freedom in doing so.

Denying the dispossessed the right to a livelihood and blaming them entirely for their own lack of ownership, on the grounds that some have more “right” to control nearly all of nature’s wealth, not only shows a lack of empathy for those who have involuntarily started life at a disadvantage compared to others, but also reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of how societal values are created. Children, the ill, and the elderly also deserve a dignified life. We must remember that one person’s needs are another’s livelihood. All value created by citizens is mutually dependent and thus, in reality, collectively generated by everyone.

A society with a guaranteed basic income for all citizens would be the optimal society founded on solidarity. Basic income is not only a way to ensure that all citizens receive a share of the collective societal value creation, which we all contribute to, but it is also a sound investment in improving the future for the country’s citizens. When all citizens have a more secure foundation, each individual becomes more resilient and thus more productive.

Providing all citizens with a basic income might seem “expensive,” but ultimately, such a scheme enriches society as a whole by giving each individual a much better starting point. When every citizen is assured an income to cover basic necessities and services, it stimulates local economies where the money is most beneficial and helps more people.

People who do not have to worry about their financial obligations have more capacity to develop themselves, their abilities, and their skills. Experiments with unconditional basic income guarantee show that people do not become less active or less productive by receiving the basic income. On the contrary, they become more capable of supporting themselves and, thus, have better opportunities to build a dignified, worry-free life in line with their dreams and desires. In short, the basic income provides people with physical, mental, creative, and economic surplus. This, in turn, enables them to make valuable personal contributions to society, enriching us all.

When everyone has financial security, there is less motivation for individuals to seek enrichment through crime to the same extent. Experiences with basic income security also show that it significantly reduces crime rates. Furthermore, it reduces healthcare costs as people are less likely to fall ill.

However, the basic income must be unconditional, for without this, it does not free people to live as free individuals on their own terms. If they are not allowed to live on their own terms, they will not achieve the same energy and motivation as they do when they can live as free individuals.

The basic income must also be “universal.” This means that everyone should have the right to basic income—both low-paid and high-paid individuals. This is crucial to prevent people from perceiving the basic income as a form of public social assistance and to avoid the stigmatisation that recipients of public assistance often experience. Instead, it should be seen as a dividend—a share of the total value created in society that all citizens are entitled to partake in. When everyone has the right to basic income, no one needs to feel inferior.

This is not communism, which involves abolishing private property and suppressing all private initiative, where no one can own anything, and everything is levelled so everyone remains at the same (low) level throughout life, and no one can stand out. On the contrary, this is about giving everyone a “starting aid” to manage themselves as well as possible. No one is prevented from starting their own business – whether small projects or larger enterprises. This is vastly different from communism, where owning businesses was forbidden and becoming wealthy from them was also prohibited.

However, it will become significantly harder for business owners to exploit labour and take almost the entire value that the workforce creates, because a society with a basic income ensures that people have the option to resign if they feel exploited, as they have the security of a basic income and no longer have to tolerate being poorly treated by their employers.

No one should have to earn the right not to be poor, just as no one in the past had to earn the right to acquire what they needed from nature to survive. We must all understand that if everyone – and not just a few – owned natural resources or shared in the value created with these resources, to which everyone originally had a right but most have lost their share in, then everyone would be far more capable of living as free individuals, much like in the past when everyone started from roughly the same starting line.

As mentioned, basic income security gives everyone the opportunity to enrich their local community and thereby themselves and the entire society for the benefit of the collective. However, we cannot achieve such a cohesive society unless everyone has the necessary empathy and care for each other and understands that no one has real freedom unless everyone ensures each other an unconditional basic income guarantee.

……………….

More info:

An Introduction to Unconditional Basic Income For All:

https://www.scottsantens.com/universal-basic-income-for-all-unconditional-why-ubi-is-necessary-now-evidence-experiments/

How to Calculate the Cost of Universal Basic Income (Hint: It’s Not As Easy As You Might Think):

https://www.scottsantens.com/how-to-calculate-the-cost-of-universal-basic-income-ubi/

Of Course We Can Afford A Universal Basic Income: Do We Want One Though?https://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2016/06/04/of-course-we-can-afford-a-universal-basic-income-do-we-want-one-though/

We can’t afford not to pay everyone a basic income:

https://www.redpepper.org.uk/we-cant-afford-not-to-pay-everyone-a-basic-income/