By Elin Brimheim Heinesen

By Elin Brimheim Heinesen

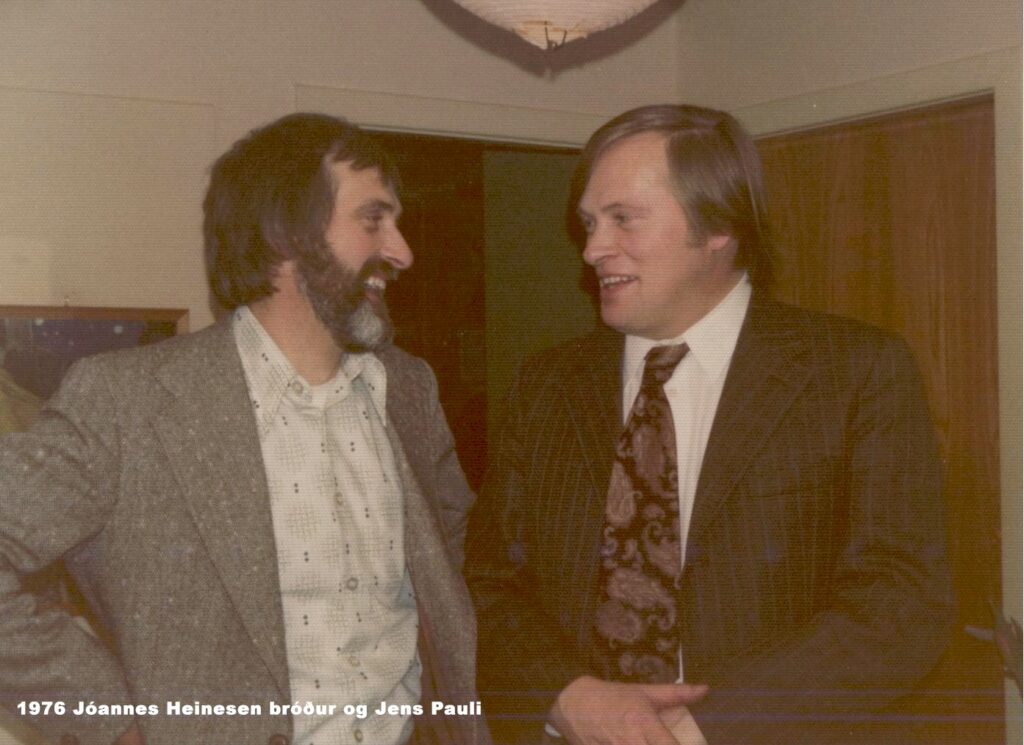

Jóannes Heinesen – also known as Jóannes á Lofti or simply Beiggi (Brother) – was born on 7th April 1930 and passed away at the Sýnini nursing home in Miðvágur on Sunday, 21st April 2024, exactly two weeks after his family celebrated his 93rd birthday. Jóannes inherited the family farm from his grandfather, Petur Heinesen á Lofti, and spent most of his life tending to meadows, mountains, and outfields, as well as keeping sheep and dairy cattle. Jóannes was married to Else Heinesen, and they had a daughter named Katrin, who has three children: Súsanna, Jóhanna, and Sámal. Jóannes was the brother of the author Jens Pauli Heinesen, my father. In addition, he had siblings Hjørdis Johansen, Klæmint Heinesen, Ásvør Ellefsen, and Hildigunn Heinesen. Jóannes was the eldest of the brothers, just one and three-quarters years older than my father, making them almost pseudo-twins.

As a little girl, I called my uncle ‘gubbi’ (godfather). But later, I also started saying ‘Beiggi’, like the rest of the family did. Yes, it was actually a bit difficult for me to decide what to call him. I can still have doubts to this day. However, there is no doubt that, no matter what he was called, Beiggi has had a tremendous impact on me personally.

The Village’s History

I have visited the village of Sandavágur countless times, spending time with my grandmother and grandfather, Beiggi, and the rest of the family there. Everything Beiggi stood for and taught me as I wandered around the village as a little girl has significantly influenced my worldview ever since. The many walks Beiggi and I took in the mountains are cherished moments etched in my memory. Beiggi would explain everything we saw. To me, his stories were like exciting adventures – about the sheep and lambs, the cattle we herded out of the farms in the morning and brought back in the evening, the birds and their nests, the mountains and nature, the village’s history and the lives of people in Sandavágur over the years. Yes, Beiggi knew every stone, every tuft, every house, and the names of everyone and everything.

Fortunately, he managed to share this knowledge with us in the documentary work “From the Mountain to the Shore,” a two-volume set he published with Heini F. Petersen, which provides a detailed account of all the place names in Sandavágur, both in the mountains and by the coast, as well as the houses and families in Sandavágur parish. I know he was particularly proud and pleased with this accomplishment. And we, as a family, are as well.

Respect for the Faroese Language and Culture

Beiggi had a special love for the Faroese language. He didn’t hesitate to correct people when they made grammar mistakes or used unnecessary Danish words. However, he did it so charmingly that no one took offence. For example, he disliked it when people said “sandavágsjingar.” “Sandavágur people!” he would correct immediately. “Oh right,” was the response, and the conversation continued cheerfully, as if nothing had happened.

Beiggi’s joy and deep respect for nature, village culture, and rural life were contagious and contributed to making Sandavágur my childhood paradise. This significantly shaped my view of the life that the Faroese have lived here for centuries, which was often hard and difficult, but also genuine and down-to-earth. For better or worse, one might say.

I remember once, when I was quite small—perhaps around four or five years old—Beiggi told a story about a lamb he found in the fields. The lamb had fallen into a ditch and couldn’t get out. It had struggled for a long time and was near death. When he helped it out, the mother sheep wouldn’t take it back. Beiggi vividly described how the lamb bleated so heartbreakingly in its loneliness and longing for its mother. But I didn’t like hearing this story. I got a lump in my throat because I felt so sorry for the lamb. Yet, I couldn’t express my feelings. So I said something like, “Don’t tell any more, uncle! It makes my throat hurt!” We’ve often laughed about that since.

A lot has happened since then. I’ve lived a very different life than Beiggi, who was a farmer and sheep breeder in Sandavágur. I spent almost a quarter of a century living in the heart of Copenhagen. It’s fair to say that was a completely different life. But in my heart, I’ve kept everything Beiggi taught me about the relationship between animals, people, and nature.

Showed Me Reality as It Was

As a little girl, I loved blood pudding. I’ll never forget the day Beiggi told me I should see how my favourite dish was made. I was six years old, and he took me out to the barn where a ram lamb was tied. It was a lamb we had raised at home, one that I had bottle-fed myself.

Beiggi explained to me that the lamb was to be slaughtered so we could have something good to eat. Even though the situation was new and a bit uncomfortable for me—I did feel compassion for the lamb—I had such great respect for Beiggi that I accepted what was happening. When my godfather said something, that’s just how it was. He acted quickly, took out the knife, and cut the lamb, causing blood to stream from its carotid artery into a bucket, which I was to stir so it wouldn’t clot.

I remember the lamb kicking its legs, and I began to wonder if it was suffering. But Beiggi assured me that the lamb didn’t feel anything. “It’s just life flowing out of it. This is how it’s supposed to be.” Alright, I thought, and accepted the explanation. A bit later, I went into the kitchen to my grandmother with the bucket full of steaming blood. She showed me how to wash the sheep’s stomach, cut it in pieces, fill the pieces with blood, fat, and raisins, and sew them up. We had a great time making blood pudding, which we ate the next day. I ate with a good appetite. I distinctly remember sitting at the dinner table that day, in my thoughts thanking the lamb for its life so I could have such a good meal.

Some may think that such things are too intense to show six-year-olds today. However, I am very grateful that Beiggi showed me reality as it was. He didn’t deceive me. He told me things as they were. In other words, he respected my intelligence. Naturally, I was clever enough to understand that this had to happen whether I witnessed it or not.

The world Beiggi showed me that day was unvarnished and true, but in my view just as magical as the Disney tales children see and hear so much of nowadays, which I often think give a distorted image of what it truly means to be human in this world. Today, children know little to nothing about where the plastic-wrapped meat they eat or the milk in cartons they drink comes from. But I knew because Beiggi showed me.

Everyone Loved Beiggi

Beiggi has always been a naturally fantastic educator without any formal training in pedagogy. He had an exceptional talent for inventing stories and, most importantly, telling them in a way that completely captivated us children. Beiggi also wrote some stories about Troll Grandma, which I read on Children’s Radio, trying to make them as vivid as Beiggi did when he narrated them to me.

I will never forget the time when we both sat in grandmother’s dining room at the table, which still stands there, and he illustrated a story for me. Beiggi explained something like this: “Once there was a strange man. He had an incredibly long nose…” and then Beiggi drew a little man with a loooong nose, stretching all the way to the other end of the paper. “And this man was married to a woman who had an incredibly long neck,” and then Beiggi drew a woman next to the man with a neck so long it reached the top of the paper. “And then there were the children… One had incredibly long legs, another had incredibly long fingers”… and Beiggi could go on like this – and I sat there, completely mesmerised, finding it all incredibly exciting.

So Much to be Grateful For

I have always held a great affection for Beiggi—just like everyone else in the family and circle of friends, because he was such a blessedly kind, pure-hearted, and good person. To me, Beiggi has been like a father—an additional father, so to speak. It was so wonderful that he called regularly—at least once a month and sometimes more often—to check on how things were going until he became senile a few years ago. For that, I am extremely grateful. It was also a true pleasure to visit Beiggi and his wife Else at Hammershaimbsvej 21 in Sandavágur, as you always felt incredibly welcome there. The hospitality and delicious food that sweet Else always served were unparalleled.

My father – known as Palli in Sandavágur – was very close to Beiggi. Beiggi was always the first person he asked about when I visited him in the nursing home in his later years. As mentioned, they were close to each other in years. The two shared a special bond as good brothers. They created a beautifully exemplary backdrop in my life, giving me the joy of seeing how much people can care for each other. Thanks to both of them, I have lived a life where – despite the bumps and bruises – I have maintained an inherent optimism and a strong belief in the goodness of people.

Thank you, dear Beiggi (or gubbi), for everything you have given me and all of us who were fortunate to know you. Rest in peace. You will be deeply missed.

Your niece, Elin Brimheim Heinesen